Guy Trebay Talks Glitter, Doom and The ’70s with Richard Boch

The New York Times style reporter and critic on his coming of age in the 1970s, his thoughts about a uniquely disjointed family life and the years running wild and occasionally lost in New York City.

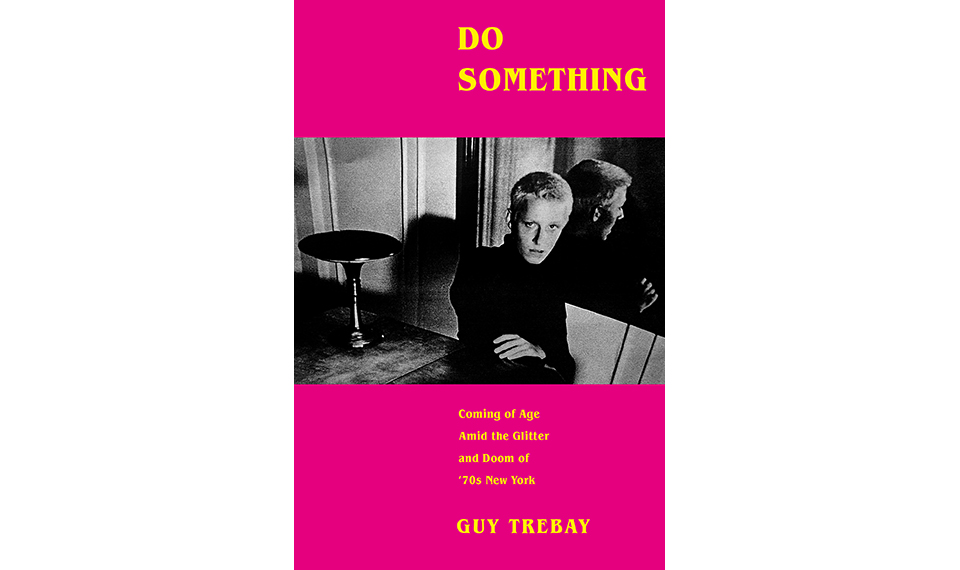

Coming of age can happen anytime, anywhere. Mid-seventies, New York City was a time before, during and after I began to experience that certain coming as it informed me, offered me identity and in some respects nearly killed me. Part of all that may well be the doom and glitter mash-up that Guy Trebay speaks of and to in the pages of Do Something, his evocative new memoir—or maybe it’s a more personal remembrance told in the darkness and light of what’s never really left behind. With its extended title, Coming of Age Amid The Glitter and Doom of ’70s New York, Trebay presents a deeply powerful look-back that both identifies and details his journey from a youthful pre-revelation to a vivid reflection on life.

There’s great joy and often great sadness in the memories we hold—and in some cases, the memories we rediscover. They live with us and they come to us as visitors, both familiar and strange. Closing our eyes, we try to see the buried images from our past. Looking at a photograph, we can either relive or reject the reality in front of us. The sharp clarity or the dreamy blur, the lost and found nature of memory has the power to haunt us, inform us and comfort us—yet we never know which until we find ourselves in its embrace.

Guy Trebay offers his memory in a single shot without chapter delineation, moving backward and forward and occasionally sideways from a critical moment in 1975. The potent mix of joy and sadness, discovery and loss, together with a jumble of family dysfunction and love, are the recollections he shares. The highs and lows are intimate yet observational, spoken with candor and precision that have the power to give us pause and reflect on our own experiences, regardless of how we may or may not identify with the story. The book’s opening-page dedication for my siblings hints at a sorrow that remains and a love that is far beyond complicated. The relationship with his parents is biographical, cherished and unforgiving, weaving its way through the pages. When New York City during the 1970s grabs hold of the story—not merely as a backdrop or set piece, but as a central character— Trebay’s memories wander through a deeply shaded yet hopeful narrative that only he could see us through. The tragedies and discoveries, as well as the shattering of a community that peaks in 1990, speaks to his compassion as a storyteller, a grieving witness and a survivor. Turning the pages of Do Something, it’s impossible to look away.

Talking with Guy Trebay about his coming of age in the 1970s, his thoughts about a uniquely disjointed family life and the years running wild and occasionally lost in New York City, is to discover the heart and soul of Do Something.

Richard Boch: Hello, Guy. We share a similar timeline as it relates to life in New York City. Our paths surely crossed, and our adjacents, as you refer to some connections, are part of the same social mix, yet we never met until a few years ago.

Guy Trebay: First, thank you for asking me to participate, Richard. I’m a fan. To answer your question, our “timelines’’ overlap owing to age and geography and I’m sure we must have crossed paths along the way. Like everyone that ever went there, I had a great time at Mudd Club in that era just before the earth cooled.

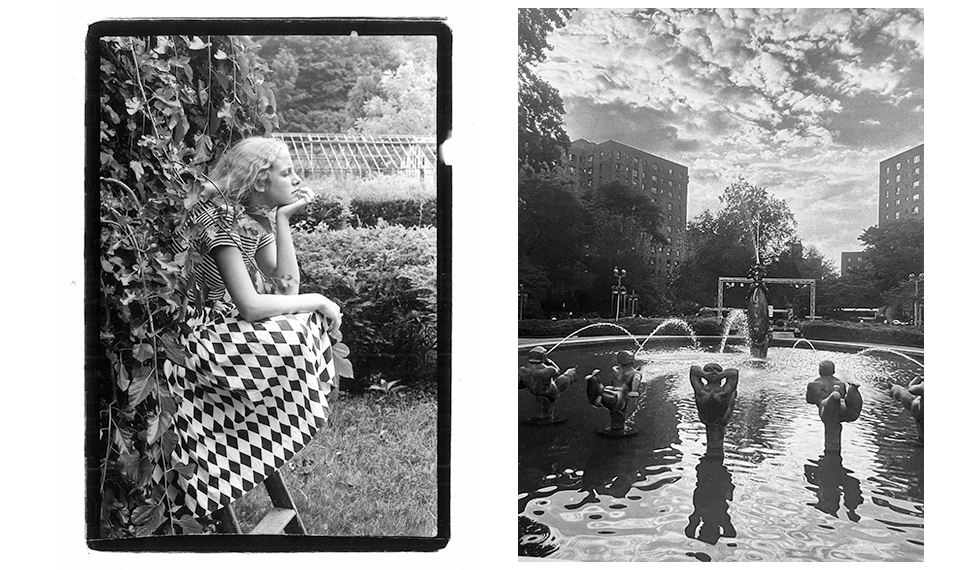

Dana Trebay, 1974. Collection of Guy Trebay; Metropolitan Oval, Parkchester, the Bronx, 2022. Collection of Guy Trebay

RB: And back then, almost everybody smoked. Pall Mall in the red soft-pack were the brand cigarettes my mother smoked, though she stopped when I was born. I believe your mother smoked a filtered version? Your father, on the other hand, created a popular men’s cologne—a distant memory for me, though for you, it’s a touchstone, a signifier of wealth and loss. Cigarettes and cologne—a combination of the two—locked together in an odd familial embrace. How do they connect, or more to the point, what’s the disconnect?

GT: It is funny you mention the comingled odors of cologne and cigarette smoke. In his review of “Do Something’’ in the Times, Andrew O’Hagan honed in on the role smells play in the book. Although that sense is so vital an element of everyday life (and is apparently the last to go) it turns up relatively infrequently in literature. I was not super-aware of focusing on it while I was writing but O’Hagan was correct. There are evocations throughout of fragrances, from my mother’s perfume (Guerlain’s Shalimar) to the reek of gasoline from a photo transfer process I was taught by Peter Beard. I think my mom’s Pall Malls were unfiltered, by the way.

RB: Before your time in New York City, I’d like to know a bit more about life on Long Island and how that life came to be for you and your family.

GT: My dad devised a men’s cologne in the 1960s called “Hawaiian Surf.’’ This was at what you could call the dawn of surf culture and the product—the bottles were encased in cork rings and there was a compass rose motif on the label—caught on quickly and became a nationwide best-seller.

My father made a lot of money very quickly and moved us as a family into a large house in Huntington Bay, Long Island, which is on the North Shore, Long Island Sound. For just under a decade, we were well-off and then my family experienced what I refer to as a parade of calamities that radically changed our lives.

Within the space of just over a year, my father’s business crashed—thanks to a partner who was an embezzler—and we lost everything. Our house then burned to the ground in a winter ice storm; my mother died suddenly of pancreatic cancer; and one of my sisters committed armed robbery, was arrested, jumped bail and went underground for the next 25 years. All of this is in “Do Something,’’ of course.

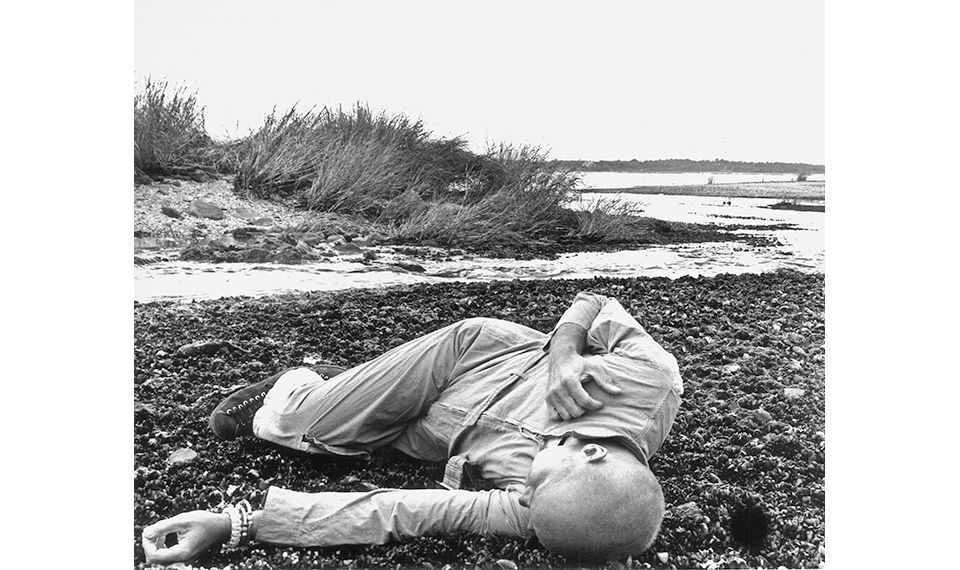

Ray Johnson, from a prophetic 1980s photo series titled Ray Johnson, Bound and Drowned. Collection of Guy Trebay

RB: The story is told with such detail that each sentence often seems to hold a story of its own. Whether writing about your parents and your siblings, the beautiful wreckage that was New York City in the 1970s or the overwhelming sadness of the AIDS crisis as the death toll peaked in 1990, your voice carries it all with a degree of detail that’s hard-hitting yet fluid and clean. Even your characterizations of the Warhol scene and downtown demimonde are detailed in a way that’s unique to Do Something. How did you manage to summon that level of detail and spin it back in such a straightforward yet very personal way?

GT: The book was written entirely from memory. I did not keep diaries or contemporaneous notes. It was only after I had a completed draft that I went back and researched the material and events. One of the challenges was that while people may fetishize the ’70s, there are few enough of us around who actually remember them—and you cannot possibly overestimate the toll taken by AIDS.

There was also the anachronism issue. Go explain to a reader of today what a 45 rpm record is… or was. Also, Google killed off memory—or at least the necessity of holding history in one’s head. Fortunately, it is also a great tool, useful provided you know where and how to look. To the extent possible, I tried to give algorithms the slip and rely instead on recollection and serendipity. I think of a designer friend who bans mood boards and instead sends students to the picture library at the New York Public Library. Her contention is that you go looking for one image and you inevitably find something better that you weren’t looking for. I love those random memory prompts. Joan Didion used to have a daffy assistant who always came back from the library with the wrong thing. Inevitably, according to Joan, whatever it was somehow turned out to be just right.

RB: As an only child, I’m fascinated when I hear someone talk about complicated family relationships, especially with their siblings. Between yourself, your two sisters and a brother, each of you were so different, though your connection, even in a spiritual sense, has stayed with you. How do you feel about those connections, and how do they speak to the very idea of family?

GT: The only way I can answer this is by reiterating something Joan (Didion) wrote to me after my younger sister’s sudden death. “In a way our siblings are our closest relationships.’’

RB: There’s a Gothic nature to the burned ruin of your family home on Long Island, including your search for the abandoned cache of family photos and the memories they hold. You were in your early twenties when you searched through that char and rubble. I can’t even imagine what finding them was like. Do you ever look at the photos today, and if so, what do you feel and see when you close your eyes and think back on those flashes of long-ago?

GT: The emotional freight of old photographs is so heavy I tend not to consult them very often. I keep a few pictures from childhood framed on my desk, but that’s it. The images in my mind’s eye are another story. They’re part of an evolving narrative. There’s a Borges quote in the book that I like about the past. I’m paraphrasing here, but Borges says that, in truth, it is not our past we recall, but the last time we remembered it.

RB: Wow! Now, that quote speaks to a great truth!

All I can say after that is thanks for taking the time to talk to me and what a great honor for you to have been included on so many Best Of and Must Read lists. Along with the beyond positive reviews and word-of-mouth, it all speaks to the success of Do Something. Any final thoughts?

GT: Gratitude is the only word. These past six months have been an amazing ride.

***

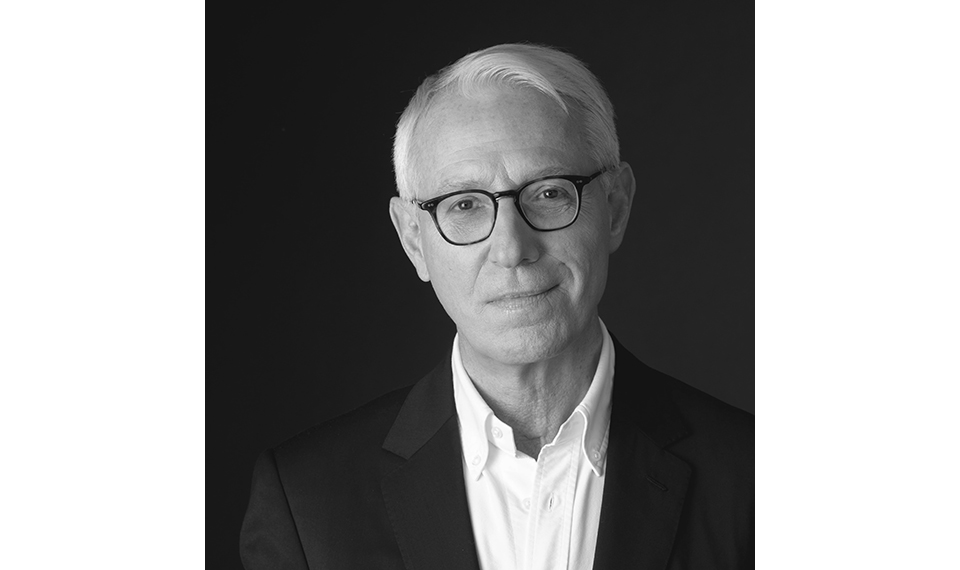

Photography © Elena Seibert

GUY TREBAY has chronicled culture, high and low, since the 1970s, writing for The New Yorker, The Village Voice, Interview, Esquire, Artforum, and many other publications. For the past two decades, he has been a style reporter and critic for The New York Times. Among his professional recognitions, Trebay has twice been the recipient of the Meyer “Mike” Berger Award from Columbia University. His work is widely anthologized, and he is the author of In the Place to Be: Guy Trebay’s New York and, most recently, his memoir, Do Something. He lives in New York.

INTERVIEW Richard Boch

PHOTOGRAPHY Courtesy Guy Trebay Knopf Publishing

Richard Boch writes GrandLife’s New York Stories column and is the author of The Mudd Club, a memoir recounting his time as doorman at the legendary New York nightspot, which doubled as a clubhouse for the likes of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Debbie Harry and Talking Heads, among others. To hear about Richard’s favorite New York spots for art, books, drinks, and more, read his Locals interview—here.